Karen Ann Quinlan

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2024) |

Karen Ann Quinlan | |

|---|---|

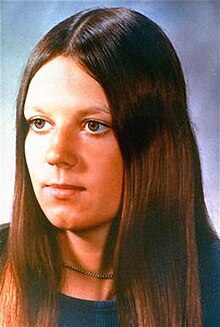

Quinlan in 1972, prior to her brain injury | |

| Born | March 29, 1954 |

| Died | June 11, 1985 (aged 31) |

Karen Ann Quinlan (March 29, 1954 – June 11, 1985) was an American woman who became an important figure in the history of the right to die controversy in the United States.

When she was 21, Quinlan became unconscious after she consumed Valium along with alcohol while on a crash diet and lapsed into a coma, followed by a persistent vegetative state. After doctors refused the request of her parents (Joseph and Julia Quinlan) to disconnect Karen's ventilator, her parents filed suit to get her disconnected. The parents believed that her still being connected constituted extraordinary means of prolonging her life.

Eventually a court ruled that the ventilator could be withdrawn. However, she continued to breathe on her own. She survived another nine years in a persistent vegetative state.

Quinlan's case continues to raise important questions in moral theology, bioethics, euthanasia, legal guardianship and civil rights. Her case has affected the practice of medicine and law around the world. A significant outcome of her case was the development of formal ethics committees in hospitals, nursing homes and hospices.[1]

Early life, collapse, and coma

[edit]Quinlan was born on March 29, 1954, in Scranton, Pennsylvania, to a young woman of Irish American ancestry. A few weeks later, she was adopted by Joseph and Julia Quinlan, devout Roman Catholics who lived in the Landing section of Roxbury Township, New Jersey. Julia and Joseph also had daughter Mary Ellen in 1956 and son John in 1957.[2] Quinlan attended Morris Catholic High School in Denville, New Jersey. After graduation, she worked at the Mykroy Ceramics Corporation in Ledgewood, New Jersey, from 1972 to 1974, and worked several jobs over the next year. Quinlan was a singer, and her parents characterized her as a tomboy.[3] In April 1975, shortly after she turned 21, Quinlan left her parents' home and moved with two roommates into a house a few miles away in Byram Township, New Jersey. Around the same time, she went on a radical diet, reportedly to fit into a dress that she had bought.

On April 15, 1975, a few days after moving into her new house, Quinlan attended a friend's birthday party at a local bar, then known as Falconer's Lackawanna Inn, on Lake Lackawanna in Byram. She had eaten almost nothing for two days. At the party, she reportedly drank several gin and tonics and took Valium. Shortly afterwards, she felt faint and was quickly taken home and put to bed. When friends checked on her about 15 minutes later, they found that she was not breathing. An ambulance was called, and mouth-to-mouth resuscitation was attempted. Eventually, some color returned to her pallid skin, but she did not regain consciousness. Quinlan was admitted in a coma to Newton Memorial Hospital in Newton, New Jersey. She remained there for nine days in an unresponsive condition before she was transferred to Saint Clare's Hospital, a larger facility in Denville. Quinlan weighed 115 pounds (52 kg) when admitted to the hospital.

Quinlan had suffered irreversible brain damage after she had experienced an extended period of respiratory failure, lasting no more than 15–20 minutes. No precise cause of her respiratory failure has been given. Her brain was damaged to the extent that she entered a persistent vegetative state. Her eyes were "disconjugate" (they no longer moved in the same direction together). Her EEG showed only abnormal slow-wave activity. Over the next few months, she remained in the hospital and her condition gradually deteriorated. She lost weight and eventually weighed less than 80 pounds (36 kg). She was prone to unpredictable, violent thrashing of her limbs. She was given nasogastric feeding and a ventilator to help her breathe.

Legal battle

[edit]Quinlan's parents, Joseph Quinlan and Julia Quinlan, requested that she be disconnected from her ventilator, which they believed constituted extraordinary means of prolonging her life because it caused her pain.[3] Hospital officials, faced with threats from the Morris County, New Jersey prosecutor of homicide charges being brought against them if they complied with the parents' request, joined with the Quinlan family in seeking an appropriate protective order from the courts before it would allow the ventilator to be removed.

Suit and appeal

[edit]The Quinlans filed a suit on September 12, 1975, to request the extraordinary means prolonging Karen Ann Quinlan's life to be terminated. The Quinlans' lawyers argued that the parents’ right to make a private decision about their daughter's fate superseded the state's right to keep her alive, and her court-appointed guardian argued that disconnecting her ventilators would be homicide. The request was denied by New Jersey Superior Court Judge Robert Muir Jr. in November 1975. He cited that Quinlan's doctors did not support removing her from the ventilator; whether or not to do so was a medical, rather than a judicial, decision; and doing so would violate New Jersey homicide statutes.[4]

The Quinlans' attorneys, Paul W. Armstrong and James M. Crowley, appealed the decision to the New Jersey Supreme Court. On March 31, 1976, the court granted their request, holding that the right to privacy was broad enough to encompass the Quinlans' request on Quinlan's behalf.

When Quinlan was removed from her ventilator in May 1976, she surprised many by continuing to breathe unaided. Her parents never sought to have her feeding tube removed. "We never asked to have her die. We just asked to have her put back in a natural state so she could die in God's time," Julia Quinlan said.[3] She was moved to a nursing home. Quinlan was fed by artificial nutrition for nine more years until her death from respiratory failure on June 11, 1985.[5][6][7]

Extraordinary means

[edit]Catholic moral theology does not require that "extraordinary means" be employed to preserve a patient's life. Such means are any procedure that might place an undue burden on the patient, family, or others and would not result in reasonable hope of benefiting the patient. A person, or a person's representative in cases where a person is not able to decide themselves, can refuse extraordinary means of treatment even if that will hasten natural death, and it is considered ethical.[8][9]

It is to that principle that Quinlan's parents appealed when they requested that the extraordinary means of a ventilator be removed, citing a declaration by Pope Pius XII from 1957.[5][10]

Life after the court decision, death, and legacy

[edit]After her parents disconnected her ventilator, in May 1976, following the successful appeal, Quinlan's parents continued to allow Quinlan to be fed with a feeding tube. Since that did not cause Quinlan pain, her parents did not consider it extraordinary means. Quinlan continued in a persistent vegetative state for slightly more than nine years, until her death from respiratory failure as a result of complications from pneumonia on June 11, 1985, in Morris Plains, New Jersey. Upon learning that Quinlan was expected to die, her parents requested that no extraordinary means be used to revive her. Quinlan weighed 65 lb (29 kg) at the time of her death.[11] Quinlan was buried at the Gate of Heaven Cemetery in East Hanover, New Jersey.[12]

Hospice

[edit]Joseph and Julia Quinlan opened a hospice and memorial foundation in 1980 to honor their daughter's memory. Her court case is linked to legal changes and hospital practices involving the right to refuse extraordinary means of treatment, even if cessation of treatment could end a life.[3]

Autopsy findings

[edit]When Quinlan was alive, the extent of damage to her brain stem could not be precisely determined. After she died, her entire brain and spinal cord were studied carefully. While her cerebral cortex had moderate scarring, it seemed that her thalamus was extensively damaged bilaterally. Her brain stem, which controls breathing and cardiac functions, was undamaged. The findings suggest that the thalamus plays a particularly important role in consciousness.[13]

In popular culture

[edit]The Quinlans published two books about the case: Karen Ann: The Quinlans Tell Their Story (1977)[14] and My Joy, My Sorrow: Karen Ann's Mother Remembers (2005).[15] In 1976 The band Starz (formerly Looking Glass) wrote a song "Pull the Plug" from their 1st studio album, "Starz", that paralleled Quinlan's story. The 1977 TV movie In the Matter of Karen Ann Quinlan was made about the Quinlan case, with Piper Laurie and Brian Keith playing Quinlan's parents.

The title character of Douglas Coupland's novel Girlfriend in a Coma[16] is Karen Ann McNeil. She collapses after a party where she has taken Valium as well as some alcohol. Like Quinlan, she has deliberately stopped eating in order to fit into an outfit (in this case, a bikini). For these reasons (and the frequent nostalgic references to events from the 1970s in Coupland's works), the character is thought to be based on Quinlan.

Donna Levin’s novel Extraordinary Means is a literary fantasy in which a young woman, although diagnosed in an irreversible coma, also brought on by an accidental combination of drugs and alcohol, is able to observe her family members debate over whether or not to withdraw life support.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ McDougall, Jennifer; Gorman, Martha (November 20, 2007). Euthanasia: A Reference Handbook. ABC-CLIO. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-1598841213.

- ^ Quinlan, J. and Quinlan, J. D. (1977). Karen Ann: The Quinlans Tell Their Story. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 0-385-12666-2

- ^ a b c d Nessman, Ravi (April 7, 1996). "Karen Ann Quinlan's Parents Reflect on Painful Decision 20 Years Later". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ Heimer, Carol (December 6, 2012). "The Unstable Alliance of Law and Morality". In Hitlin, Steven; Vaisey, Stephen (eds.). Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Springer. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-1441968951.

- ^ a b Stryker, Jeff (March 31, 1996). "Right to Die; Life After Quinlan". The New York Times. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ "Karen Ann Quinlan dies after 10 years in a coma" Archived 2015-10-24 at the Wayback Machine, St. Petersburg (FL) Evening Independent, June 12, 1985, p. 1

- ^ In Re Quinlan 355 A.2d 647 (NJ 1976)

- ^ McCartney, James (1980). "The Development of the Doctrine of Ordinary and Extraordinary Means of Preserving Life in Catholic Moral Theology before the Karen Quinlan Case". Linacre Quarterly. 47 (215).

- ^ Coleman, Gerald (March 1985). "Catholic theology and the right to die". Health Progress. 66 (2): 28–32. PMID 10270328.

- ^ Scheb, John (March 28, 2011). Criminal law. Wadsworth Publishing. p. 85. ISBN 978-1111346959.

- ^ McFadden, Robert (June 12, 1985). "Karen Ann Quinlan, 31, Dies; Focus of '76 Right to Die Case". The New York Times.

- ^ "Tearful Rites for Karen Quinlan", Bergen Record, June 16, 1985. Accessed August 4, 2007. "A procession of about 75 cars then drove to Gate of Heaven Cemetery in East Hanover."

- ^ Kinney H. C.; Korein J.; Panigrahy A.; Dikkes P.; Goode R. (1994). "Neuropathological Findings in the Brain of Karen Ann Quinlan – The Role of the Thalamus in the Persistent Vegetative State". The New England Journal of Medicine. 330 (21): 1469–1475. doi:10.1056/nejm199405263302101. PMID 8164698.

- ^ Quinlan, Joseph; Quinlan, Julia; Battelle, Phyllis (1977). Karen Ann: the Quinlans Tell Their Story. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-12666-3. OCLC 3259340.

- ^ Quinlan, Julia (2005). My Joy, My Sorrow: Karen Ann's Mother Remembers. Cincinnati, Ohio: St. Anthony Messenger Press. ISBN 978-0-86716-663-7. OCLC 58595022.

- ^ Coupland, Douglas (1998). Girlfriend in a Coma. Toronto: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-224396-4. OCLC 37983572.

External links

[edit]- Karen Ann Quinlan Hospice

- Karen Ann Quinlan at Find a Grave

- Sabatino, Charles P. "Advance Directives and Advance Care Planning: Legal and Policy Issues". American Bar Association Commission on Law and Aging. Archived from the original on September 16, 2008. Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- 1954 births

- 1985 deaths

- American adoptees

- Medical controversies in the United States

- Morris Catholic High School alumni

- People with severe brain damage

- People from Scranton, Pennsylvania

- Deaths from pneumonia in New Jersey

- People from Byram Township, New Jersey

- People from Roxbury, New Jersey

- American people of Irish descent

- Burials at Gate of Heaven Cemetery (East Hanover, New Jersey)

- People with disorders of consciousness

- People with hypoxic and ischemic brain injuries

- Famous patients